Twenty years ago Liechtenstein’s attack on Germany

On 1 June 2001 the Alpine Principality brought an unusual case before the UN Court of Justice for the use of its assets as war reparations

It was on June 1, 2001, a Friday exactly twenty years ago, that the Principality of Liechtenstein instituted a sensational legal proceeding before the International Court of Justice against Germany over a dispute concerning the far-reaching legal, social, moral and economic effects of the Second World War.

For the first time in history, the Federal Republic of Germany was in fact called upon to answer alone, before the 15 magistrates elected for nine years in the Peace Palace in The Hague, the main judicial organ of the United Nations, for the conduct of its internal authorities at the request of another sovereign state.

Professional titles more equivalent between Switzerland and Germany

The subject of the dispute, which was of extraordinary political and normative interest, also in light of the growing importance of the issue of the restitution of works of art between countries following theft or requisitions in the past, concerned Germany’s decision to unilaterally treat property allegedly belonging to Liechtenstein citizens as German property confiscated for the purpose of compensation for war damage suffered by others.

The Czechoslovak “Beneš Decrees” between Berlin and Vaduz

The appeal of the Alpine Principality recalled that a series of measures adopted by Czechoslovakia in 1945 and subsequently implemented by the Czech Republic and Slovakia today, the so-called “Beneš Decrees”, provided for the confiscation of the property of German and Hungarian citizens located on their territory and that the government in Prague also applied these rules to other natural or legal persons whom it considered in its sole discretion to be of German or Hungarian origin or ethnicity, treating Liechtenstein citizens as German nationals.

Summary of the centenary love between Switzerland and Liechtenstein

Czechoslovakia was a country sided with the Allies and belligerent against the Third Reich during the Second World War, however the practical effect of its post-war political choices was that the rules strongly advocated by Edvard Beneš (a very important figure for Prague in the period of transition between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Soviet bloc… ) led to the seizure of property owned by the Liechtenstein state and the ruling house itself, which had remained on Czech and Slovak territory and had never been returned to its rightful owners or the subject of an offer or payment of compensation for confiscation.

The appeal to the Hague by the Principality stated, “the decisions of Germany, in 1998 and after 1998, to treat certain assets of Liechtenstein citizens as German assets having been ‘seized for the purpose of reparation or restitution, or because of the state of war’ – i.e. as a consequence of World War II – without ensuring any compensation for the loss of such assets to their owners, and to the detriment of Liechtenstein itself.”

Comparison between the five German-speaking countries in Lugano

The two German-speaking countries and a 1957 Convention

As a basis for the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, Liechtenstein invoked the European Convention for the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes of 29 April 1957, ratified by Bonn on 18 April 1961 and by Vaduz on 18 February 1980.

According to Article 1, the contracting parties “shall submit to the judgment of the International Court of Justice all international legal disputes which may arise between them, including, in particular, those concerning: (a) the interpretation of a treaty; (b) any question of international law; (c) the existence of any fact which, if established, would constitute a breach of an international obligation; (d) the nature or extent of reparation to be made for the breach of an international obligation”.

First visit to Switzerland of the new Premier of Liechtenstein

The move by the Principality, which in 2001 had no diplomatic relations with either Prague or Bratislava because of old disagreements, was in some ways legally risky. Was Germany its “enemy” or rather the former Czechoslovakia?

It was fair to ask this question on the basis of the principle of the “necessary third party“, now affirmed by international courts of all kinds and rank. The Czech Republic was in fact not a party to the European Convention for the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes, so it could not be said to have consented to the jurisdiction of the Hague Court under that treaty.

Is the “necessary third party” principle necessary and diriment?

Despite the fact that Article 32(1) of the Treaty provided that it “shall remain applicable as between the parties, even if a third State, whether or not a party to the Convention, has an interest in the dispute,” the Court would have administered the “necessary third party” rule independently in determining whether it had jurisdiction to hear Liechtenstein’s claim.

The historical context of the dispute was quite clear, beyond the pronouncements that would follow. In 1946, Czechoslovakia confiscated property belonging to citizens of Liechtenstein’s rank, including Prince Franz Josef II himself, on the basis of legal provisions authorizing the expropriation of “agricultural land” (including buildings, installations and movable property) of “all persons belonging to the German and Hungarian people, regardless of their nationality”.

Europe remains the “second home” of the Swiss abroad

A special regime with regard to German assets abroad and other German property confiscated in connection with the Second World War had also been created by the sixth chapter of the Convention on the Settlement of Questions arising from War and Occupation, signed in 1952 in Bonn.

According to Vaduz, this only concerned the property of the German state or its citizens and, due to the undisputed neutrality of Liechtenstein and the absence of any connection between the Principality and the conduct of the war by the Third Reich, did not apply to Liechtenstein property affected by Allied measures.

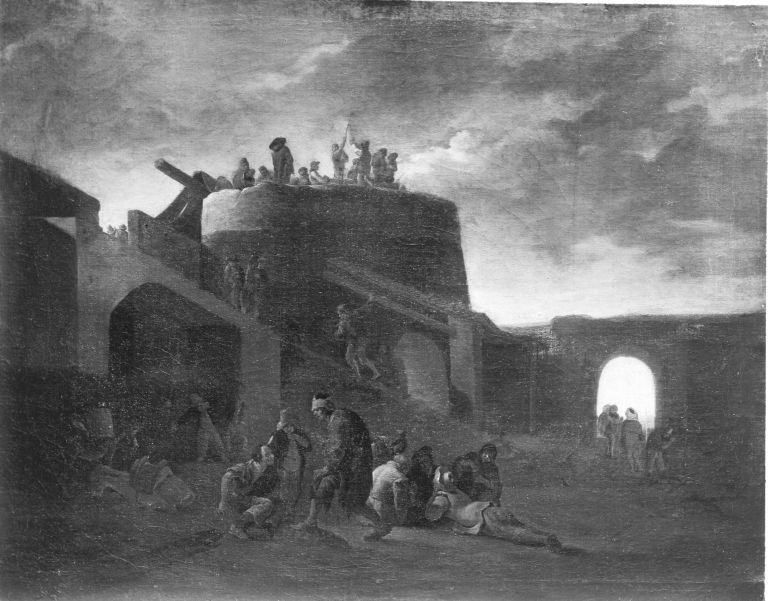

The intrigue of Pieter van Laer’s painting six years ago

In 1991, however, it happened that a painting by the Dutch master Pieter van Laer was loaned by the Office of Historical Monuments in Brno to the City of Cologne for inclusion in an art exhibition.

The painting “Szene an einem römischen Kalkofen” (“A Roman Lime Quarry” in Italian) had been owned by the family of the ruling princes of Liechtenstein since 1767, but since 1946 it had been in the complete possession and purported ownership of the Czechoslovak government.

Switzerland and Liechtenstein in full agreement about the future

Prince Hans-Adam II von und zu Liechtenstein, acting in his personal capacity, then instituted proceedings in the German courts to have the picture returned as his property, but these proceedings were rejected on the grounds that, under Article 3, Chapter 6, of the aforementioned 1952 Bonn Convention (paragraphs 1 and 3 of which are still in force), no claim or action in respect of measures taken against German property abroad in the period after the Second World War would be admissible in the German courts.

The prince argued that the picture had not been the subject of expropriation measures in the former Czechoslovakia and that in any case such measures were not valid or irrelevant because of the violation of the public order of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Nothing to do for Hans Adam II in Cologne and Karlsruhe

Even a complaint lodged by Her Majesty with the European Court of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms in Strasbourg regarding the decisions of the Cologne courts of first and second instance (Tribunal and Court of Appeal) was rejected between 1995 and 1996, as well as two and three years later in 1998 in Karlsruhe by the Bundesverfassungsgericht, the Federal Constitutional Court.

The German judiciary had thus become totally levelled with the Czechoslovak judiciary: in 1951 the Administrative Court in Bratislava had rejected the appeal filed by Franz Joseph II, considering him to be a person of German nationality, in accordance with the provision of Article 1, letter a, of the Decree 12/1945 in force in Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia.

Bern-Berlin alliance on coronavirus APPs

After public hearings on Germany’s preliminary objections in June 2004, the UN International Court of Justice issued its ruling on February 10, 2005.

The Hague began by rejecting the Germans’ first preliminary objection, which argued that the UN Court lacked jurisdiction because there was no dispute between the parties.

A matter to be settled with the Czech Republic and Slovakia

The Court then examined Berlin’s second objection, which asked it to decide, in the light of the provisions of Article 27(a) of the European Convention for the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes, whether the dispute concerned facts or situations which arose before or after 18 February 1980, the date on which that Convention entered into force between Germany and Liechtenstein.

Switzerland-Liechtenstein pact on scientific innovation

The Hague judges concluded that, although the proceedings had been instituted by Liechtenstein following decisions of German courts concerning a painting by Pieter van Laer, the facts in question had their origin in specific measures taken by Czechoslovakia in 1945, which led to the seizure of property belonging to certain citizens of the Principality, including the then sovereign Franz Joseph II von und zu Liechtenstein, as well as in the special regime created by the Convention on the Settlement of Matters Arising from War and Occupation, and that the real source or cause of the dispute was therefore to be found in the latter and in the “Beneš Decrees” in force in Czechoslovakia.

An excerpt from the judgment of the International Court of Justice of February 10, 2005 (In English)

The UN Court accepted Germany’s second preliminary objection by twelve votes to four, noting that it could not rule on Liechtenstein’s claims on the merits, and thereby concretely stating that the matter should be settled between the governments of Vaduz, Prague and Bratislava, without bringing the German courts into play…

Tägermoos, and a very old treaty between Baden and Thurgau…