Don’t ask us for words: in Italy we no longer have any…

The evolution of the bureaucratic language of the Belpaese does not move towards simplification, but towards farce: an idiom which, by now, is only a hypocritical jargon

In 1525, Pietro Bembo, one of the most refined intellectuals of the Renaissance, published a small treatise in the form of a dialogue, destined to have an enormous influence on the Italian language and literature: the “Prose della volgar lingua”.

We will overlook the fact that, nowadays, more or less no one finds themselves consulting the agile booklet: the fact is that, from then on, our way of writing has changed, our language has stabilized on a stylistic model played out between the prose of Giovanni Boccaccio and the poetry of Francesco Petrarca and Tuscan has become and remained the mould with which to give form to our verbal expressions.

For some time now, however, the lesson of Bembo, as well as that of many of his followers, up to Alessandro Manzoni who, in a certain sense, crystallized these choices, is undergoing important and significant changes.

That politically correct thinking that makes Italian into meatballs

In its eagerness to shape Italy, a certain kind of thought, politically correct, is making meatballs of our language, introducing a whole series of new idiomatic forms, of metalanguage, of hypotypes with a distressing ethical value.

Ever since some smart-ass discovered that words are not only stones, but can also be caresses, there has been a succession of Arcadian academies, of shepherd’s workshops, of candy-colored syntactic and semantic goodness, to give diabetes to all the glottologists in the universe.

And it was all a flourish of the blind, the differently abled, the cognitively fragile.

However, I believe that the most interesting linguistic metamorphosis and, if you will allow me to say so, the most hilarious and grotesque, has been that of the bureaucratic language of the school, which, from the daring morphosyntactic inventions of 1968 to today has, so to speak, constantly adapted its language to this “glucose Weltanschauung”.

From “flunking” schoolchildren in red letters to… Reorientation

I’ll give an example that applies to everyone. At the end of every school year, throngs of anxious parents and worried pupils have always crowded outside Italian schools to read their fate on the infamous display boards: authentic proscription lists, on which the eye of the unfortunate scrolled, to discern salvation or ruin.

Once, the dreaded word “failed” appeared in a beautiful vermilion red: it stood out in the black lists of those who had been promoted and immediately jumped out at you.

The logic was probably to shorten the painful search. You knew it and off you went!

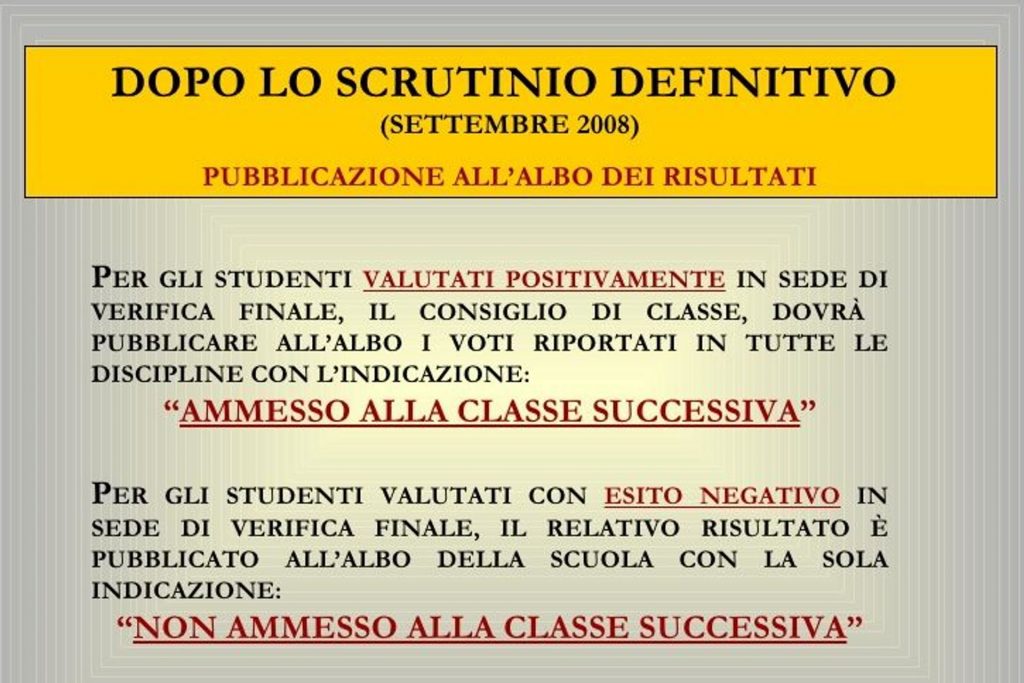

Then, in Viale Trastevere, they must have said to themselves that that peremptory sentence, so prominently displayed, really did evoke Dracone or Silla: adelante Pedro, but con juicio! So, they switched to the formula “Not promoted”, in black, without any evidence.

But even that must have seemed too demeaning a formula and smelled of appeals, protests, simple discontent.

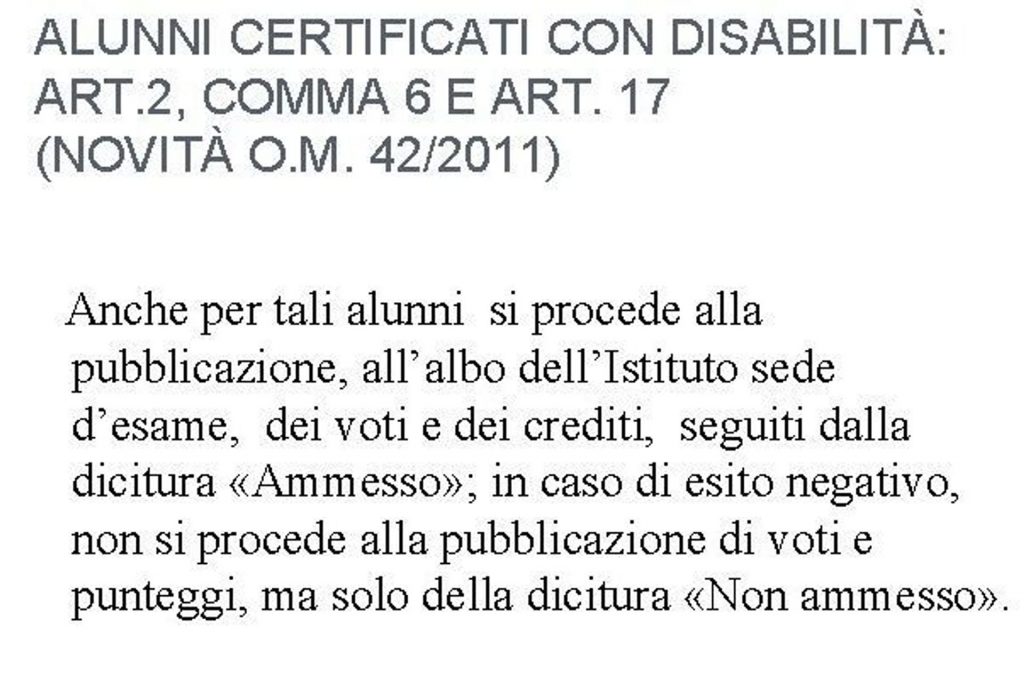

The ambiguous formula of “not admitted”, with equal destiny

So, they opted for a lower-profile “Not admitted”: the reality did not change, but the condemned person even ran the risk of not understanding his fate, given the ambiguity of the formula. He had time to metabolize his grief, in a sense.

Today, instead, is the latest, caricatured, version of the Italic rejection: the very few unfortunates who fail to be promoted, in this school that, by now, is somewhere between a fun fair and a shelter, will be “reoriented”.

On the boards, in short, will be written “Reorientation”, which evokes bickering, desert expeditions, tropical cruises: everything except a healthy, invigorating, rejection.

The student will repeat the year and will, in fact, fail, exactly as before and as always.

But do you want to put when, to the fateful question about how he went to school, he can proudly answer: “Reoriented”? With the peace of Messer Bembo.