The inhumanity of the first revolutionaries germ of catastrophes

On the anniversary of the Révolution Française, it is time to ask serious historiographic questions about what it really represented

Revolutions, you know, must necessarily be violent: they are not a gala dinner and their corollary of death and abuse is, so to speak, the obvious calling card.

All of them, none excluded, have claimed their tribute of blood: whether it was the Cavaliers of 1649 or the Barins of 1917.

Therefore, it is not for the size of the massacre that, today, the French Revolution should be reread and recommented: certainly, it was a massacre, but the twentieth century has seen much worse massacres made in the name of a revolutionary principle.

The wonderful (as unrealized) dream of isonomy

The “modernity” of an idea: principles are worth more than people

The point is that it was the French Revolution that gave rise to the entirely modern idea that principles are worth more than people: that, in a certain sense, human beings are simply symbols, to be destroyed or exalted, depending on their political or social position.

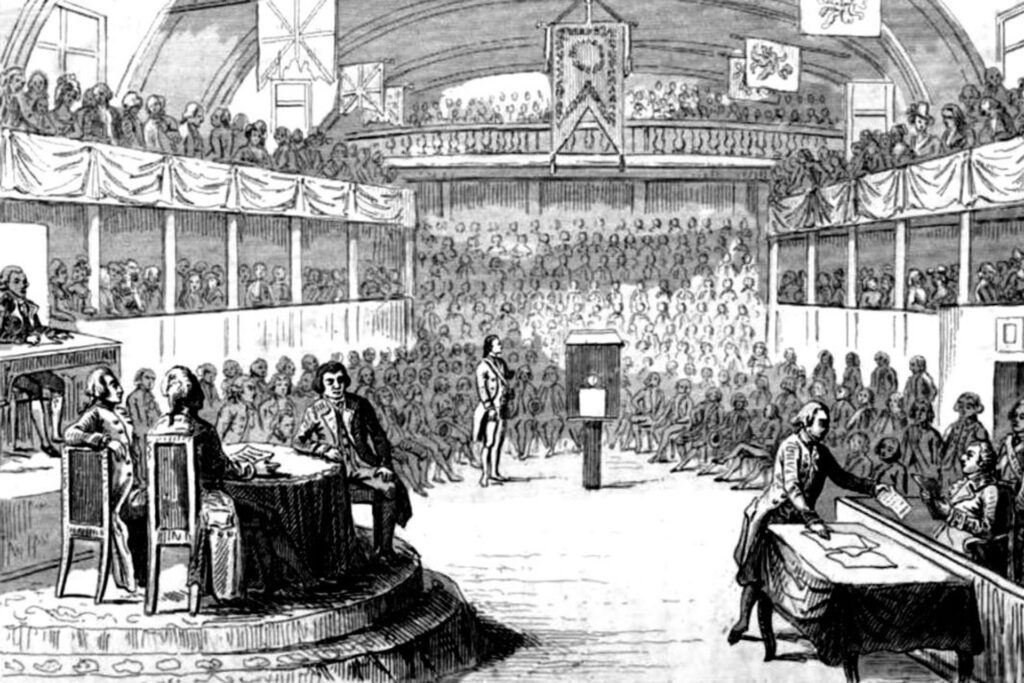

In short, in 1789 the inhumanity of the revolution was affirmed for the first time. Not cruelty or bloodthirstiness: those already existed. Just the inhumanity: the lack of feeling in applying the law of extermination.

Because killing without hating is something that leaves you speechless: the theorization of terror, its bureaucratization, is something that goes beyond the simple crime.

A (conformist) society of shame ready for oblivion

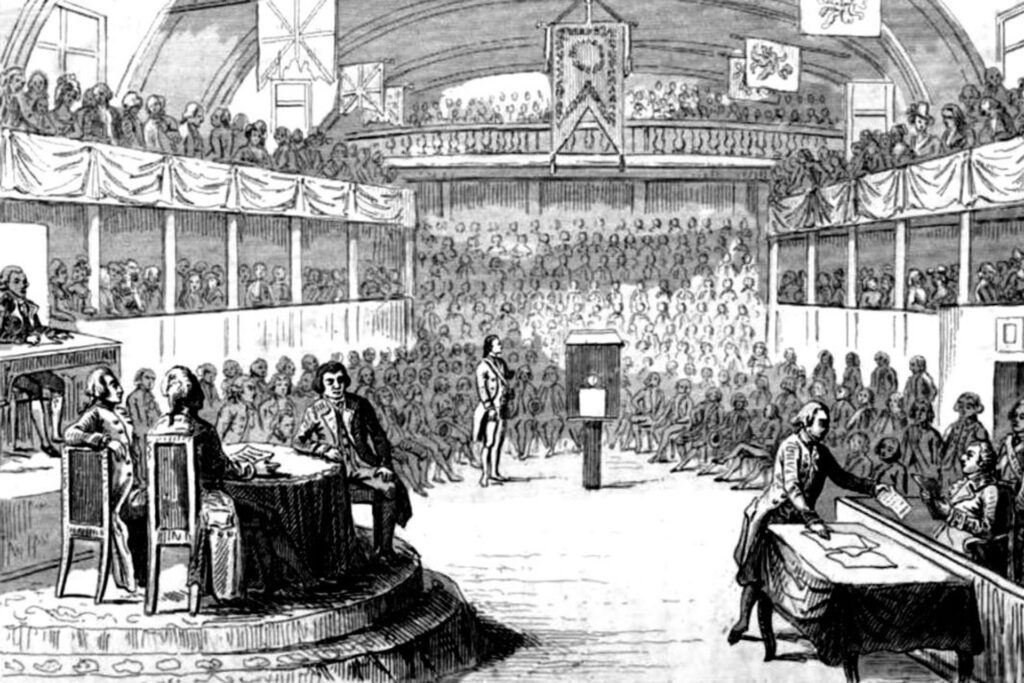

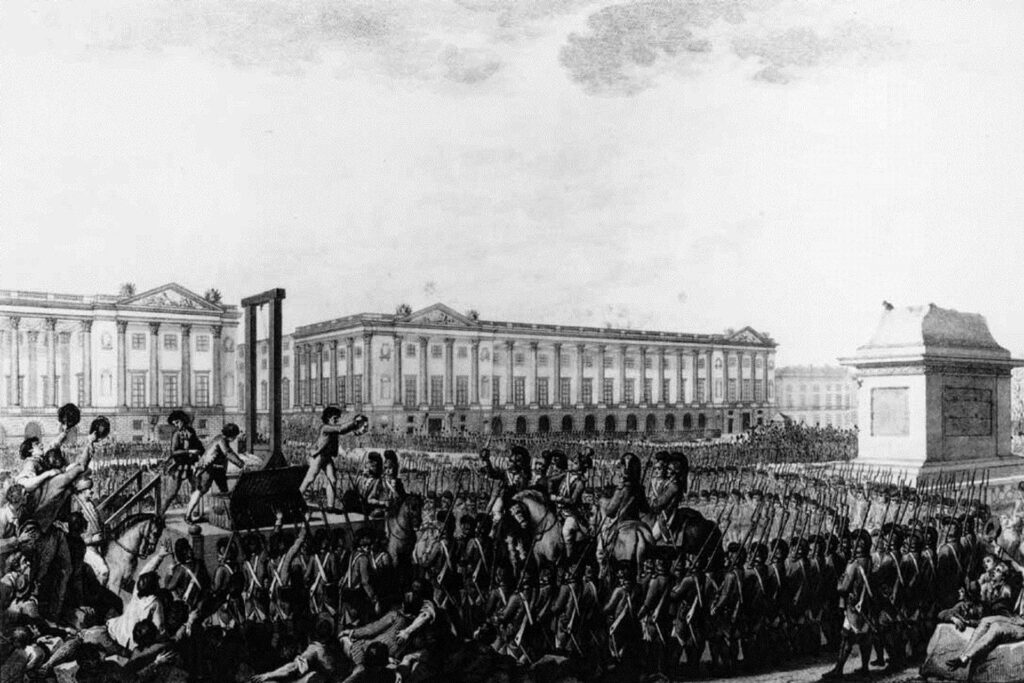

From Robespierre or Saint-Just, the political necessity of the crime

So, we can say that Robespierre or Saint-Just have been the models on which have been shaped, in the following centuries, the great revolutionaries, but also the great criminals against humanity.

The brigatists who shot saying they were killing a symbol and not a man: in the meantime, however, they were killing fathers, brothers, someone’s sons. And they justified themselves with this disconcerting lack of feelings: with this Jacobin idea of political necessity of the crime.

From Habsburg Verantwortung to ostentatious irresponsibility

Armenians, Kulaks, Jews and Cambodians in a single bloodbath

It was so for the Armenians as for the Kulaks, for the Jews as for the Cambodians: numbers in the balance sheet of the genocide. And, round and round, everything originated from the French Revolution: the great matrix of modern exterminations.

For this reason, the years of the revolution and, above all, those of the Terror, should be studied from this point of view: that of the epistemology of massacre.

It was then that those aberrant theories began to take shape that have found full application in the colossal massacres of modernity and that are undoubtedly daughters of the Jacobin experience.

Of course, the material executors of the massacres must be counted among the bestial creatures: the devil’s columns or the tricoteuses represent patent forms of degeneration of humanity.

Even a wrong idea of State can generate holocausts

The cold and rational cruelty in applying an unjust law

But the instigators, the ideologists, the children of progress who, convinced of being free, equal and fraternal, created the law of suspicion or sent hundreds of people to death every day, for the sole guilt of being part of the hated aristocratic class, those represent a different phenomenon: the cold cruelty in applying an unjust law is something very different from the animalistic reactions of the unleashed plebs.

Just that coldness, that aseptic cruelty, is the worst consequence of the French Revolution: a consequence that we can recognize in all modern genocides and classicides. Because it is the unmistakable stigma.

The unsustainable and eternal stupidity of the censorship algorithm

From 1789 onwards the dangerous primacy of theory over reality

Ultimately, the French Revolution introduced to the planet the idea that theory can supplant reality: that, in the name of the former, we can erase the latter. Even if reality has the form of a human being.

Therefore, simplifying a bit, I would like to write that the “Absolute Evil”, which today’s democrats like to evoke so much, should not be sought in the ferocious totalitarianisms of the twentieth century, but much further upstream, in the crazy and disastrous years of revolutionary France.

What if Soccer is the most reliable social marker?