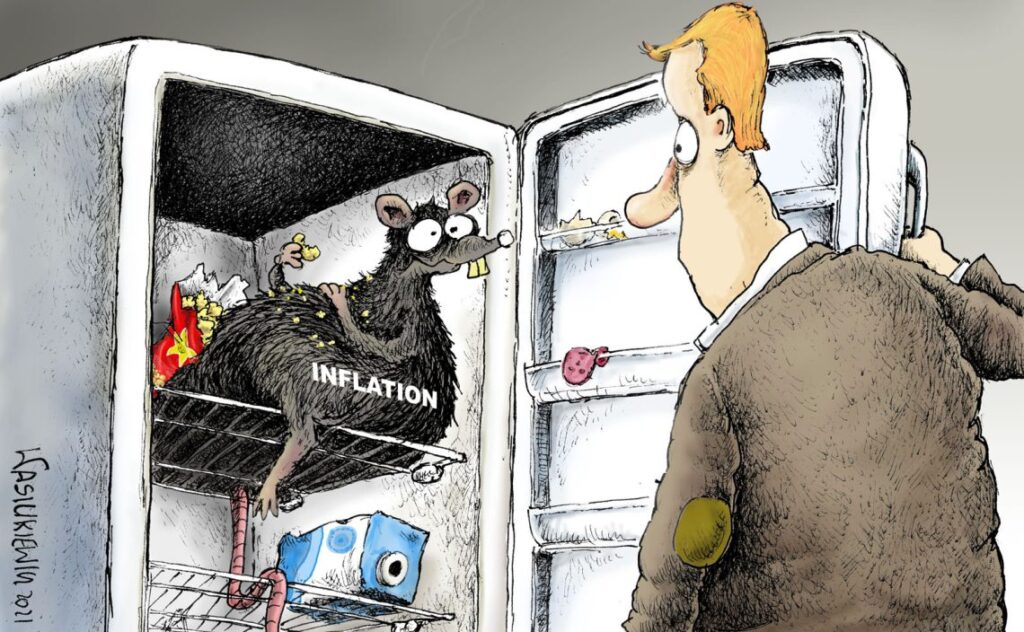

Inflation: Causes and consequences

GIS has long warned that inflation was around the corner – not due to Covid or war, but because of profligate monetary policy

In a nutshell

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Inflation is the result of poor economic policy

- Irresponsible leaders have pursued easy money as a solution to economic woes

- Governments continue their disastrous, unsustainable spending habits

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The last few years have witnessed severe, even frightening, developments: the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and government reactions to it, Russian aggression in Ukraine and its influence on energy and food supplies, as well as economic turbulence – most disturbing among them the rapid rise in inflation.

Mainstream analysis puts the blame for inflation squarely at the feet of the other two phenomena. The explanation they offer is simple: the pandemic, combined with war, has led to inflation and further economic upheaval.

The true cause is very different. Inflation is a result of poorly informed policy and intervention, introduced at every level of the economic ladder by authorities who ignored the possibility of unintended consequences. In some cases, unsuccessful reformers or cynical politicians have used it as an excuse for their own failed policies.

GIS, however, has been analyzing these developments for years, and foresaw the consequences long before they finally appeared. GIS’s independent experts have frequently dived deep into these matters, and exposed economic mismanagement at every step of the way.

Europe’s problem is too much government and too much regulation

As far back as seven years ago, GIS Founder and Chairman Prince Michael of Liechtenstein warned about the specter of inflation in his comment entitled “Currency war is destructive to global economy and trade,” published in February 2015:

The European Central Bank’s policy of easy money and quantitative easing is outpacing the U.S. Federal Reserve, which is indicating that it will tighten monetary policy in the future. …

Europe’s problem is too much government and too much regulation. But instead of addressing these problems, Europe – with the help of the ECB’s monetary policy – is experimenting with QE and zero to negative interest rates.

Unfortunately, the money generated does not flow down to business. Business lacks the confidence to invest and many banks lack sufficient equity to increase their loan portfolio. As a consequence of QE, the euro is becoming unattractive and declining as a result of this policy – whether intended or not.

This raises Europe’s competitiveness in export markets in the short term, although imports are becoming more expensive. But it does not force an increase in productivity and real competitiveness in innovation, quality, and process optimization in the economy. …

A short cyclical decline would not be such a problem. But this appears to be a structural policy combined with the inflation target.

Another comment by Prince Michael from March 5, 2016, reminds us that certain solutions – pushed by policymakers all over the world – did not bring the intended effects:

For years policymakers in governments, central banks and academia have preached easy money and inflation as a solution to the economic woes in Europe, the United States and Japan. But years of administering this medicine have had no effect on growth. Instead, it has led to an asset bubble, damaged savings (especially retirement funds) and motivated governments to delay painful but necessary reforms.

In July 2017, Prince Michael continued to point out how irresponsible policymakers were implementing dangerous solutions.

President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi has also changed his focus. Instead of seeing the lack of inflation as the main cause of insufficient growth, he has begun blaming inequality as the root of the problem.

This is very confusing. First, the flood of cheap money due to quantitative easing promoted “inequality” by hugely inflating asset prices. The influx of cheap money was used to buy shares, companies and real estate. This demand caused increased prices and valuations.

An economy that grows mainly due to abundant, cheap money is a bit like a drug addict.

Nevertheless, the ECB continued to lament the lack of inflation. Prices of company shares and real estate skyrocketed, artificially and on paper, causing a larger concentration of wealth with fewer people. The low (and in some cases negative) interest rates also hit people with savings in banks. This inequality was widely caused by central banks’ policies. As this bubble is bound to burst eventually, a leveling off will take place – but at a very high cost.

Cheap money today, a disaster tomorrow

A year later, the global situation seemed to have reached a tipping point, but again the main actors were surprised by the consequences of the solutions they had implemented. Moreover, they were interested in treating the symptoms and not the root causes. In a July 2018 comment, Prince Michael concluded:

The growth in recent years has been largely driven by consumption. Unfortunately, this was, to a non-negligible extent, due to abundant consumer and housing credit based on cheap money, provided by the central banks in nearly all major economies. At the same time, most governments did not take the opportunity to reduce their deficits, but continued high levels of spending and increased their countries’ debt.

All major central banks arrived at the limit of their ability to reduce interest rates (being already near zero or below) and have begun to talk of “tapering.” The U.S. Federal Reserve has already started, while the European Central Bank announced its more than 2.6 trillion-euro bond-buying program would end in September. Believing in the magic that some 2 percent inflation enhances growth, the officials at the ECB have concluded that this goal has finally been reached, so they can also slowly increase interest rates.

However, there are two problems: First, even if we believe in the 2 percent magic, this figure is mainly driven by an increase of 8 percent in energy prices and some 3 percent in food prices. Significantly, core inflation rose by just 1 percent.

But what really aggravates the situation is this: an economy that grows mainly due to abundant, cheap money is a bit like a drug addict. It cannot function without an additional money supply – it always needs more, or else it collapses.

The world is arriving at the possible end of a growth cycle, while households and governments have not just empty pockets, but also a high debt burden. At the same time, the central banks have used up all their ammunition. The necessary and overdue increase in interest rates will be disastrous for budgets, both public and private.

Causes of inflation older than pandemic

More than a year after the pandemic began, in February 2021, Prince Michael lamented how already spendthrift governments had become even more profligate, and were exerting even greater control over populations:

Even before Covid-19 struck, many governments had dangerously high debt levels. Now that they have been given a new excuse to spend, the public sector is becoming even more bloated. Such a strategy will prove unsustainable in the long run, and inflation will inevitably appear. But meanwhile, states keep on expanding their influence, wielding more and more power over citizens.

In the same comment, he went on to – again – accurately predict the coming wave of inflation:

The pro-debt economists, politicians, and media forget what money is: a means of exchange for goods and services and a mechanism to store value between transactions. Sound money is based on the value of all underlying transactions. If the volume of money drastically exceeds this amount over a long period of time, its inherent value will be eroded.

Even if many modern economists deny it, inflation will appear. We have already seen, as a result of the virtually nonexistent cost of capital and interest rates, incredible inflation of assets, including real estate, equities, company participation, art and so forth. This artificial increase in value explains much of the increasing inequality, ultimately the price of having an oversized government.

Although most low and middle-income households were already feeling pressured before the pandemic, the prices of consumer goods have not yet started rising sharply. The reason for this is twofold. First, the new money remained in the financial system (with the asset inflation and rising on-paper inequality mentioned above). Second, businesses became more efficient and productive, offering products of improved quality and some more environmentally friendly products at the same price, which is a type of healthy deflation. But this situation may not last. …

Food prices are key indicators, and they can affect political stability when they spiral out of control.

In recent times, the money supply in the eurozone has increased by some 15 percent per year, while pre-Covid GDP was growing at a rate lower than 2 percent – a significant disparity. Fewer and fewer people are employed in the productive part of the economy in relation to the public and compliance sectors. It is also worth noting that, in Europe, the number of people entering the workforce is not high enough to compensate for the rate at which people are retiring. And SMEs, the backbone of the economy, are suffering, sometimes even closing, because of Covid-19 lockdowns. Inflation appears to be around the corner.

In June 2021, Prince Michael pointed out that food prices were rising rapidly, usually a harbinger of inflation and proof that the previous predictions were accurate:

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) publishes a monthly Food Price Index. The figures for May 2021 are alarming. Food prices always vary, as they depend on harvests and the weather. But the index shows an increase of some 4.8 percent since April 2021 and 39.7 percent compared to May of last year. This rise was caused by several factors, including production costs, currency issues, weather changes, variations in demand, and the use of maize for biofuel. The prices of cereals, vegetable oil, dairy, meat and sugar saw the largest increases. It is possible that the price of food commodities will fall again. But this would be unlikely in the near future, due to more demand. Protectionist policies, trade disputes and sanctions could exacerbate the situation.

A short-term rise in food prices could trigger an outbreak of inflation that would go far beyond the 2 percent mark. Lower prices of oil and gas would not offset these higher prices, and the transition to renewables will likely increase the cost of electricity.

Once inflation starts, it is very difficult to rein in. Food prices are key indicators, and they can affect political stability when they spiral out of control. The Arab Spring started in Tunisia and Egypt because of higher food prices.

Today’s loose monetary policy will not keep inflation at 2 percent. Traditionally, purchasing power is preserved and prices stabilized by adjusting interest rates and taking liquidity out of the financial system. However, under the pretext of fighting the consequences of Covid-19 and stimulating a “green economy,” even more money is being pumped into the system. If interest rates were to increase, the financial position of the already bankrupt governments would become untenable.

Inflation could be welcomed by some cynics in policymaking, as governments might be hoping it will lower the cost of their debt. But in practice, this would be a hidden tax that would mostly affect the poor. From a mathematical standpoint, inflation reduces debt. But if this “debt relief” comes, it can easily get out of control and government expenses will likely rise as well. As a result, societies would be burdened with both debt and inflation.

In recent years, the official inflation statistics in the Western world showed stable prices. However, consumers were already being affected by the erosion of their purchasing power. The basket of goods and services used as the basis of the index was not necessarily representative. …

The irresponsible spending policy of most states, in combination with overregulation, market interventions and oversized governments, was never sustainable and will inevitably lead to major depression. Covid-19 has accelerated this process.

The success of Western economies, especially European ones, was driven by small and medium-sized family businesses. They lent resilience to increasingly fragile societies and economies. While many governmental institutions are still overblown relics of the 19th century, the business environment has evolved. The innovative spirit fostered by free markets led to prosperity. But now inflation will hurt this stronghold.

New challenges

Finally, inflation reared its ugly head. And for readers of GIS, it was no surprise. It was not the result of the pandemic or the conflict in Ukraine. Instead, it was the consequence of many years of shortsighted policies and misunderstood measures, as Prince Michael had predicted.

Fear of inflation is spreading globally. After an extended period of asset price inflation (during which the concern for general inflation was downplayed), now consumer price inflation is hitting 4 percent in Europe and 5 percent in the U.S. A normal monetary policy reaction would be to take liquidity out of the system. Central banks would increase interest rates and minimum reserves. Since the European Central Bank (ECB) and the U.S. Federal Reserve are currently financing governments directly by purchasing their bonds – a risky move that is against their statutes – the central bankers could, in theory, also reduce these purchases, which is called “tapering.”

Raising interest rates increases the debt-servicing burden of the overextended countries. But what about tapering? Last week, ECB President Christine Lagarde expressed the policy wryly and clearly: “The Lady is not for tapering.”

So, inflation will rise further, fueled by the irresponsible policies of governments running deficits and central banks pumping more and more money into both the economy and governments. This vicious circle also allows the public sector to expand further.

There is already concern about who will pick up the tab.

Expansive monetary policy has been maintained for several years now. Politically, it is motivated on both sides of the Atlantic by the desire to avoid natural downward shifts in the economy and populist politicians’ unsatiated need for money to satisfy their clientele with handouts. As a result, the public sector’s spread has no end. This nefarious process is combined with hectic regulatory work at the national and supranational levels. The rising wave of regulations and legislation generates the need for more staff to administer, control and enforce. In this context, enterprises big and small must allocate ever more resources to comply with the new rules, not all of them productive, but all of them increasing the cost of doing business. Firms’ productivity is reduced, and the cost of an expanding headcount must be passed on to clients and, ultimately, all consumers. Prices then increase. …

The phenomenon of the growing state has been with us for a long time. However, businesses in many countries have been doing a tremendous job innovating and increasing productivity. That had a positive deflationary effect, compensating for the inflationary activities of governments and central banks. Now, it seems that a tipping point has been reached. The economy’s strength is no longer sufficient to outweigh the proliferation of the public sphere and its associated costs, as well as the burden of expansionary monetary policies.

Until recently, policymakers frivolously lamented that inflation rates were below 2 percent, the magic formula for healthy growth. Well, 2 percent has been reached, and surpassed, over the last three months. Inflation is likely to keep on rising out of control. Rather than help expand the economy in the medium and long term, it gives rise to the worst, which is stagflation: persistent high inflation combined with high unemployment and stagnant demand. …

The situation we are in today is, most emphatically, a result of gross mismanagement. Geopolitical Intelligence Services has warned in many reports and comments of the danger, but policymakers have treated inflation as a solution. …

Economists on supranational and national levels may not be unhappy, as the responsibility for the disaster will become unclear. But the consequences will be dire: savers will lose their money without seeing the political leadership taking it in obvious ways. Prosperity will be rolled back; social problems will grow. But, as the cynical reasoning goes, so will the power of the state and the political establishment.

However, the technocrats may miscalculate. Citizens have ample reason to rebel and bring drastic changes in the political systems. This ill-advised journey propelled by cynical, self-serving policies, technocratic arrogance and populist lies can end in turmoil.

The first victim of inflation is the middle class. At this point, it looks likely that the inflationary policies will continue, and the lower-income groups will be kept loyal to the bankrupt system through further handouts and propaganda blaming the rich. Wealth and inheritance taxes are likely to rise in this context, even though we know empirically that these are detrimental to the overall economy and prosperity. The end result is social and political trouble. …

Political classes, opinionated technocrats and some economists have taken this refuge for more than a decade now. Today, the dilemma is how can one make governments, administration and supranational organizations leaner and return more workforce talent to the productive side. This is one of the daunting socioeconomic challenges of our time.

Source: