That Italian Confederation born and buried in Zurich

The Piedmontese violation of the Peace between Austria and France of November 10, 1859 denied the Peninsula an alliance led by the Pope and endowed with a common army

A Confederation of Italian States presided over by the Pontiff was not only evoked by the political thought of the philosopher Vincenzo Gioberti, but it was very close to becoming a reality after the Second War of Independence.

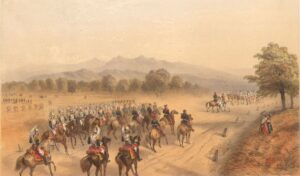

On July 11, 1859, after the battle of Magenta and the bloody battles of Solferino and San Martino, Napoleon III, in his quality of Emperor of the French, and Francis Joseph of Hapsburg, his Austrian counterpart, signed the Armistice of Villafranca.

The act should have put an end to the Savoy and Piedmont’s attempt to expand towards the East and to the aims on Venice cultivated since a long time by Cavour, circumstance that forced the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Sardinia to give immediate resignation.

The “reluctant” signature of the King of Sardinia

Although in Villafranca di Verona on the following day 12 Vittorio Emanuele II, who wanted to annex the whole Lombardy-Venetia Kingdom, signed the armistice, it was mainly due to the unilateral will of France not to extend the conflict to Central Europe, a demand that was immediately accepted by Austria.

Alexandre Colonna Walewski, Minister of Foreign Affairs, had in fact communicated to Napoleon III “the warning” that had come to him indirectly from St. Petersburg from the government of the Czar of Russia, for which if the Sardinian-French army had insisted on fighting and violated the territory of the German Confederation, which could have happened in Trentino, even only with Giuseppe Garibaldi’s volunteers, the Kingdom of Prussia would have entered the war with the other German States against France.

Negotiations between the powers begin in Switzerland

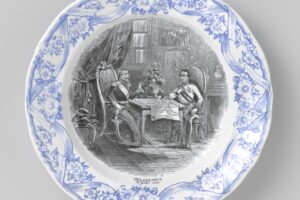

On August 8 in Zurich opened the peace conference, where the Habsburgs did not want the presence of the Piedmontese plenipotentiaries. France was represented by Count Bourqueney and the Marquis of Banneville, Austria by the Baron of Meysembug and Count Karoly, the Kingdom of Sardinia by the knight Louis Des Ambrois de Nevâche.

As a matter of fact, the negotiations were conducted only by France and Austria, who easily reached an agreement: Lombardy, with the exception of Mantua, a fortress of the fortified quadrilateral whose vertices included also Verona, Peschiera del Garda and Legnago, was given to France and Piedmont could only accept or refuse the “gift” of the back passage of this region.

The treaty, with a proterity that today would not have been tolerated with regard to the non-observance of an international agreement (“Europe is asking us for it”), was not respected by the Turin government, which ignored the provisions clearly stated in articles 18 and 19 of the Zurich Peace of November 10, 1859. The address of the unification of Italy took place in a decidedly monarchical and unitary sense, making federalist ideas fade away.

Il Trattato di Zurigo tra Austria e Francia del 10 novembre 1859

The Pontiff honorary president of the union

On the whole, the pact would have prefigured a federation of states and a common army on the US or Swiss model, the confederal presidency entrusted to the Pontiff, the participation of Austria in it as holder of the sovereignty over Veneto, the safeguard of the rights of the states of Tuscany, Modena and Parma and the confirmation of the prerogatives of the Church over the so-called Legation of Romagne: Bologna, Ferrara, Ravenna and Forlì.

Article 18 stated: “His Majesty the Emperor of France and His Majesty the Emperor of Austria undertake to favour with all their efforts the creation of a Confederation between the Italian States, which will be placed under the honorary presidency of the Holy Father, and the purpose of which will be to maintain the independence and inviolability of the confederated States, to ensure the development of their moral and material interests and to guarantee the internal and external security of Italy with the existence of a federal army”.

And again, reading the second paragraph on this issue, concerning the destiny of Veneto, it said: “Venice, which remains under the crown of His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty, will form one of the States of this Confederation, and will participate in the obligations as well as in the rights resulting from the federal pact, whose clauses will be determined by an assembly composed of the representatives of all the Italian States”.

Without prejudice to the rights of Tuscany, Modena and Parma

Article 19 saved the survival of secular feuds, which insisted on the current territories of Emilia and Tuscany: “The territorial districts of the independent states of Italy, which did not take part in the last war, not being able to be changed that with the concurrence of the powers that have presided over their formation and recognized their existence, the rights of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, the Duke of Modena and the Duke of Parma are expressly reserved between the high contracting parties.