What if Russia cuts off gas to Europe? Three scenarios

Europe is ill-prepared for a large-scale disruption of Russian gas supplies, making it vulnerable to arm-twisting in the event of a conflict in Ukraine

Since last summer, Europe has been in the midst of a natural gas supply crisis – a bind that an escalating Russia-Ukraine crisis only makes worse.

It is normal for Russia to provide more gas to Europe than is contractually obligated, especially when prices and demand are high. Yet even though European gas consumption increased by about 5.5 percent and prices hit record highs, Russia refrained from pumping any extra gas into the continent. European countries typically use this extra gas to fill their storage facilities during the summer. Russian President Vladimir Putin himself has repeatedly put pressure on Europe, especially Germany, to quickly approve the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project (which bypasses Ukraine), and to sign new long-term gas delivery contracts as preconditions for supplying additional gas to Europe.

The move seemed part and parcel of Moscow’s hybrid war against the West (the European Union in particular) and Ukraine. If the Kremlin does decide to invade Ukraine, triggering sanctions by the EU and United States, it could retaliate by cutting gas supplies – potentially by crippling amounts.

Weaponizing gas exports

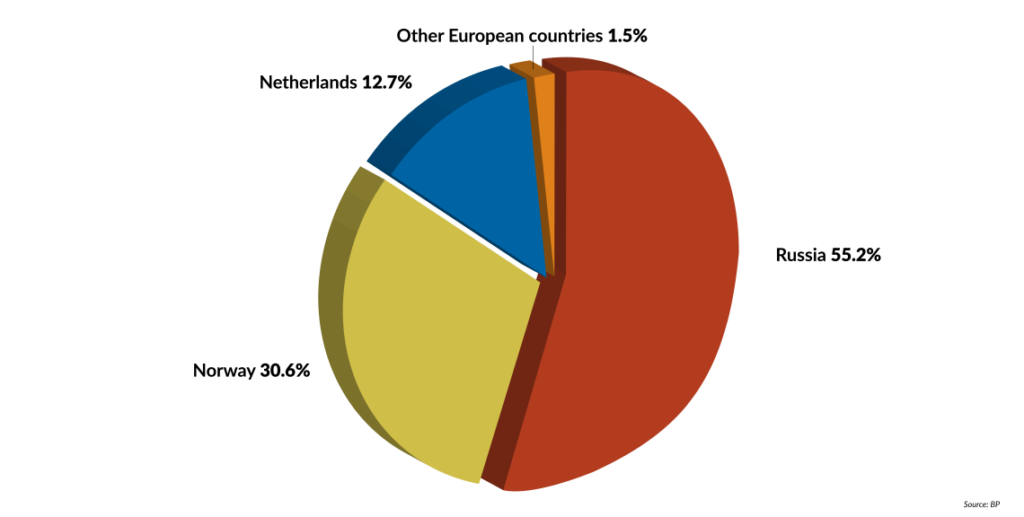

Natural gas accounts for about 20 percent of Europe’s primary energy consumption, as well as 20 percent of its electricity generation. It is also used for heating and industrial processes. Russia is Europe’s largest gas supplier, delivering an estimated 168 billion cubic meters (bcm) to the continent (including Turkey) in 2021, short of its own projections of 183 bcm. In the last months of 2021, Russia delivered only 19 bcm through Ukraine – less than half of the agreed 40 bcm capacity, during a time when deliveries should have been increasing due to the onset of winter. Some worry that in a wider conflict between Ukraine and Russia, these deliveries could be severely disrupted, potentially for months or years.

A resurgence of global gas demand and bottlenecked supplies are the original causes of high energy prices in Europe, but President Putin’s insistence on refilling Russian storage sites last September before sending any natural gas to Europe has not helped matters any. Though the Kremlin denies it, many in Europe see the move as extortion aimed at twisting Germany’s arm on Nord Stream 2.

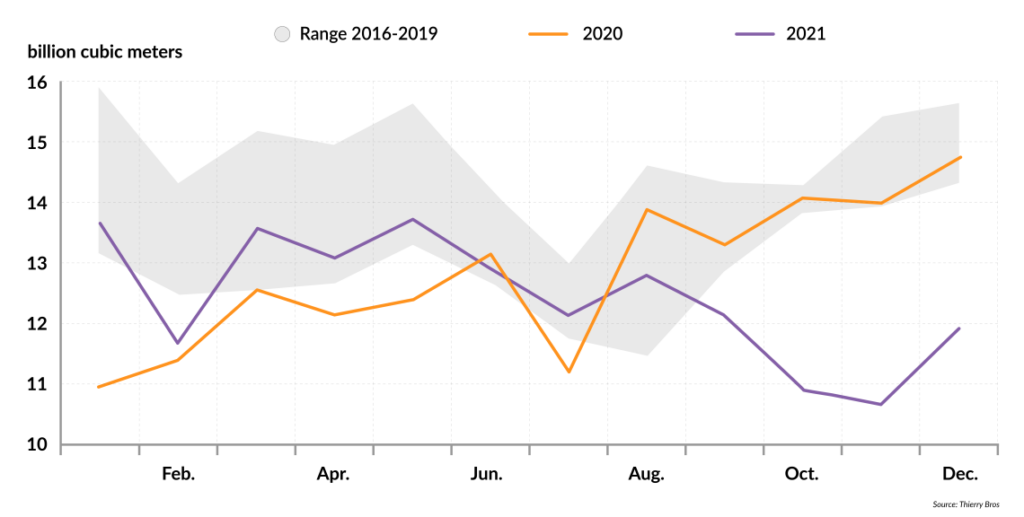

Despite record high prices, Russia’s gas exports to Europe in 2021 remained lower than they were in 2019. Europe’s gas storage facilities became depleted during the winter months, their levels falling to historic lows, and may run empty by March or April.

“Despite record high prices, Russia’s gas exports to Europe in 2021 remained lower than they were in 2019”

Moscow’s decision to limit gas supplies to Europe through Ukraine (and Belarus) added to European market turbulence and helped keep gas prices high. Critically, Russia does not need completion of Nord Stream 2 – which still awaits the approval of the German regulators and then the European Commission – to increase its gas supplies to Europe. Plenty can come through existing pipes. Russia pumped some 104.2 bcm through Ukraine to Europe in 2011, and as much as 89.6 bcm in 2019.

Aside from Nord Stream 2 approval, Moscow wants European gas companies to sign more long-term delivery contracts, binding them to Russian supplies at fixed prices for 10-20 years. In contrast, those firms prefer signing flexible, short-term spot contracts, which have usually been cheaper in recent years. By the end of 2020, spot contracts accounted for 87 percent of all gas delivery contracts in Europe.

Moscow’s argument that Gazprom needed to replenish Russia’s gas storage facilities before increasing supplies to Europe was undermined when it turned out that they were nearly full by October 20, holding 69 bcm out of a total 72.6 bcm. In the fourth quarter of 2021, Russian gas supplies to Europe were 25 percent lower than in the same period of 2020. By the end of January 2022, European gas storage levels had fallen to below 40 percent of their capacity. At the time, Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency, criticized Russia for exacerbating Europe’s gas crisis, accusing Moscow of restricting the gas it could send to Europe by at least a third.

Dependence increasing

Since the EU introduced its “Third Energy Package” in 2009, the bloc has taken numerous measures to enhance its gas supply security. It has expanded its liquefied natural gas (LNG) import capacity to 237 bcm per year, including 29 large-scale gas import and regasification facilities, new gas interconnectors between EU member states, and the completion of the TANAP-TAP pipeline network to import gas from Azerbaijan.

“The EU’s options to make up for a gas shortfall are limited”

All of this has improved the EU’s gas security, leading some governments and experts to believe that the issue is now closed. If the Kremlin were to deliberately disrupt gas supplies, the thinking goes, the EU would simply import more LNG, which could be distributed throughout the entire European gas market. As a result, Germany increased its reliance on Russian pipeline imports from 42 percent in 2010 to 55 percent in 2021. The EU’s gas dependence overall has been increasing rapidly as well – including Russian LNG supplies, the bloc went from receiving nearly 44 percent of its gas from Russia in 2020 to 53 percent in the fourth quarter of 2021.

The idea that Europe could compensate for a disruption in Russian supplies was based on the assumption that a buyer’s market would remain in place, with suppliers scrambling to win over customers. However, lower gas production due to the pandemic and China’s rapid economic recovery since autumn 2020 has shifted the supply and demand balance toward a seller’s market, with global gas shortages and rocketing prices.

Scenario 1: Ukraine supplies disrupted

If a war breaks out and the gas that the EU currently receives from Ukraine is cut off, the bloc would have limited options to make up for the shortfall. The Netherlands is a major gas producer, but in 2018 the Dutch government decided it would halt all production by the end of 2022. In January, Berlin asked it to deliver an additional 1.1 bcm, even though it had previously blocked a new Dutch offshore gas project that would have bordered Germany. For now, the Netherlands is obliging, but its phaseout is still on track.

Other alternative supplies are also problematic. Norway, Europe’s second-largest gas supplier, has increased its deliveries, but would be unable to make up for a significant disruption. In December it suffered an unplanned outage at a key gas field, restricting shipments.

Algeria is Europe’s third-largest gas supplier, but its deliveries to Spain have decreased due to an ongoing conflict with Morocco. Azerbaijan is unable to increase its gas production in the short term, so Europe cannot count on more gas through the TANAP-TAP system.

The EU could compensate by importing more LNG, of which the United States is its biggest supplier. In 2019 the U.S. delivered some 25 percent of all of the bloc’s LNG imports. The U.S. will have the capacity to export some 118 bcm per year by the end of 2022, and more than 160 bcm per year by 2024. In the event of a crisis, some 15 percent of global LNG exports could be redirected to make up for a European shortfall. Prices would rise even higher, though.

Scenario 2: Russia cuts supplies by half

Under this scenario, Russia would only maintain its direct gas pipeline supplies via Nord Stream 1 (capacity: 55 bcm per year) and both Turk Stream pipelines (combined capacity: 31.5 bcm per year). In doing so, Russia could maximize its gas revenue but divide the EU into member states receiving its supplies (Austria, Bulgaria, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, the Netherlands), those that are cut off (Lithuania, Poland), and those that can receive the gas they need as long as they toe Russia’s political line (the Czech Republic, France, Italy).

Despite having an LNG import capacity of around 1,900 terawatt-hours (TWh) and only using 730 TWh of that in 2021, the EU would face huge challenges finding sufficient LNG supplies to compensate for a Russian supply cut of 50 percent in the short term – particularly during a colder winter in Asia and Europe.

Spot and short-term LNG contracts accounted for 38 percent of the global LNG market in 2021. Still, in the Asia market specifically, LNG imports are overwhelmingly based on long-term contracts. Supplies from the U.S. intended to fulfill these contracts could only be rerouted in the event that demand is unexpectedly low – for example, if there were an unusually warm winter.

“The EU gas market is still not designed to fully supply the region from the west”

This actually happened in December 2021, when mild weather in Asia meant that 34 tankers with U.S. LNG switched routes from Asia to Europe, helping to bolster the latter’s storage levels. In January, Europe went from using 51 percent of its LNG regasification capacity to 75 percent (Only 90 percent of a terminal’s capacity can be used). In Western Europe, it used all of its available capacity, leaving free import capacity only in Eastern and especially Southern Europe. Some increased supplies from the U.S. are likely to be forthcoming in the short term. Other than the U.S., Australia seems to be the only major LNG supplier able to raise its LNG exports in the coming months. Aside from that, the rerouting of spot market LNG supplies will help, whereas the redirection of long-term LNG cargoes will remain dependent on the demand and weather in Asia.

Some analysts estimate that Europe could replace as much of two-thirds of the gas received through Russian pipelines with seaborne LNG. That assessment could be overly optimistic. Central and Eastern Europe lacks sufficient gas interconnectors to make the plan work. Spain and France have a similar problem. And Germany has no LNG import terminal at all. Member states have their own gas infrastructure systems that are often built to transport gas of different qualities and chemical compositions, limiting the ability to simply pump gas from one country to another. Even with expanded LNG import terminals and numerous interconnectors in Eastern Europe, the EU gas market is still not designed to fully supply the region from the west of the bloc.

Russia has the fourth-largest foreign exchange reserves in the world at about $630 billion, meaning it could easily survive a longer-term cut in supplies. And at the rocketing prices such a cut would cause, Moscow could make up a sizable portion of the difference by increasing sales to other customers. In contrast to the EU, Russia introduced a comprehensive economic-financial strategy after the West introduced sanctions over its annexation of Crimea. That has helped it reduce its dependence on the bloc.

Europe, by contrast, would struggle to compensate for the disruption quickly, forcing it to ration and reduce gas consumption. That would not only affect energy generation and heating, but also cripple gas-intensive industries.

Scenario 3: Russia halts all gas supplies to Europe

This scenario is the least likely, since it would ruin Russia’s relationship with the EU and destroy any notion that it is a reliable supplier of gas. It could also eliminate any hope it has of becoming a significant exporter of hydrogen to the EU as well.

But if it did occur, Europe would be in a tough spot. Replacing all Russian pipeline gas would require a quarter of the global LNG production in 2021. Again, any significant rerouting of LNG supplies would depend on the weather in Asia. Spot-market contracts would not be able to make up for the 170 bcm per year of Russian pipeline gas that Europe would lose. Some 62 percent of all global LNG contracts are governed by medium- and long-term contracts.

“Europe’s overdependence on Russian pipeline gas has become one of its biggest strategic weaknesses”

European industry would be severely disrupted. Electricity would be rationed, potentially leading to frequent blackouts – with all of the negative effects that would have on critical infrastructure. Considering this scenario highlights how Europe’s overdependence on Russian pipeline gas has become one of its biggest strategic weaknesses.

Strategic perspectives

A complete supply cut to Europe would cost Gazprom between $200 million and $230 million per day. If that disruption were to last three months, the lost sales would add up to less than $20 billion, which Russia could easily cover with its $630 billion in foreign reserves and any gains from new sales to other regions at higher prices. This year, Gazprom is expected to make more than $90 billion in gross operating profit compared to just $20 billion in 2019.

The ability to curtail the flow of natural gas remains the Kremlin’s most important and effective leverage against Europe, whether it comes to avoiding sanctions or influencing the EU’s reaction to an escalating Ukraine conflict. It also shows how the interdependency between Russia and Europe is asymmetric. Russia can survive harsh economic sanctions from the West for at least a year, if not longer. The EU would be in serious trouble if Russian gas supplies were cut – even by just 50 percent – after a few months. It simply has not sufficiently diversified its sources of gas imports and has underestimated the value of energy security weighed against climate-friendly policies and cheaper gas supplies.

As journalist and energy expert Llewellyn King put it in a column for Forbes in November: “The gas buyers of Europe and their political masters bet that Russia needed their market more than they needed Russia’s gas. … Europe has bet wrongly on the spot market, Russia, and the wind. Just about everything that could go wrong, has gone wrong.”

Author: Frank Umbach

The editorial contribution comes from the information and research site “Geopolitical Intelligence Services” (GIS) of the Principality of Liechtenstein