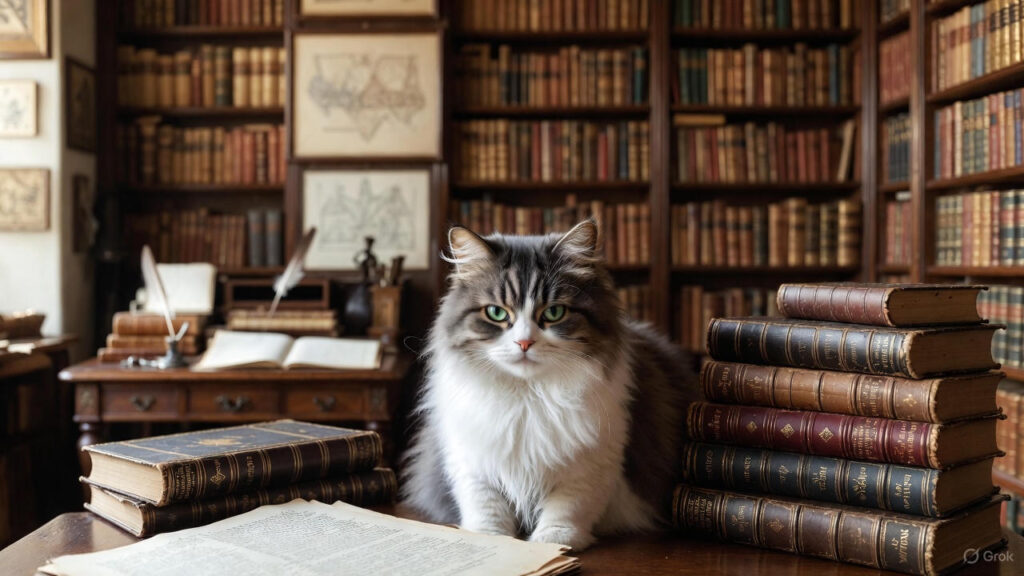

The knowledge-guarding cats

Back when mice were the scourge of libraries, the most dependable remedy had four legs and purred.

Long before the digital age and well before air conditioning, high-resolution scanners, or international archival standards existed, libraries around the world had a common enemy: mice. Attracted to paper, parchment, and the animal glue used to bind books, these rodents posed a constant threat to entire cultural collections. The response was surprisingly universal: cats were enlisted as official guardians of knowledge. This tradition spans European medieval monasteries, Asian libraries, Middle Eastern temples, Islamic archives, Chinese imperial palaces, and, of course, cultural institutions in Switzerland, Italy, Russia, and the United States.

A global problem: mice vs. manuscripts

From ninth-century Ireland to Edo-period Japan, from the Caliphate of Córdoba to the Ottoman Empire, the scene was always the same: a single mouse could destroy in one night what generations of scholars had spent years creating. In Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries across Europe, in Japanese Zen temples, in madrasas of the Islamic world, and in the palaces of the Forbidden City, rodents knew no cultural or religious boundaries. Wherever knowledge was stored on organic materials—paper, parchment, bamboo, or leather—the risk was the same.

Official feline teams in service

Cats thus became part of the staff, often with official recognition:

-

In medieval Europe, they already appear in monastery accounting records, with expenses listed for milk and fish.

-

In Ottoman libraries, specific funds were allocated for the care of cats.

-

In Russia, Peter the Great and later Catherine II ordered the transfer of cats from Kazan to St. Petersburg to protect the manuscripts of the Hermitage—a tradition that continues today with the famous 70 “Hermitage cats,” employees of the Russian state.

-

In Japan, Buddhist temples regarded cats not only as practical guardians but also as spiritual protectors.

-

In 1880, the British Library officially paid six pence a week to its cats serving as “rodent officers.”

Even the United States Library of Congress employed cats until the 1970s.

Success for the presentation of the book Il coraggio è femmina at the Italian Chamber of Deputies

Cat flaps: architecture in the service of felines

One of the most poetic signs of this global alliance are cat flaps: small doors or openings built into the doors of libraries and archives, allowing cats to patrol freely even when the rooms were closed. They can be found:

-

In English and French monastic libraries of the 13th and 14th centuries

-

In the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence and the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice

-

In the Swiss archives of St. Gallen and Einsiedeln

-

In Tibetan and Japanese monastic complexes

-

In some historic madrasas of the Middle East

Small doors for great rescues.

The swiss cat ladder phenomenon

Cats who made history (literally)

-

Pangur Bán (9th century), the cat of an Irish monk celebrated in the oldest European poem dedicated to a library feline.

-

Mike (1907–1929), chief cat of the British Library, buried with full honors in the museum courtyard.

-

The cats of Topkapı, Istanbul, who for centuries protected the manuscripts of the sultan’s palace.

-

The Hermitage cats, who during the Siege of Leningrad (1941–1944) were the only unit never evacuated; when the cats died of starvation, an entire train from Yaroslavl arrived to replace them.

-

Browser (Texas), Elsie (Minnesota), Kuzya (Moscow): modern library cats with ID cards, Instagram pages, and thousands of devoted readers.

A heritage we owe to them

How many works by Aristotle, Avicenna, Averroes, Dante, Galileo, or the Zen masters do we owe, indirectly, to the nocturnal vigilance of a cat? Without their silent work, entire chapters of human intellectual history would have been lost—not to censorship or fire, but to the tiny teeth of rodents.

A lesson for the present

Today, books are increasingly digitized, rodents are kept at bay by environmental control systems, and archives are protected by advanced technologies. Yet the history of library cats leaves us with a simple and profound lesson: the preservation of knowledge has always been a collective endeavor, in which even the smallest and seemingly most insignificant actors can prove decisive.

Sometimes, the future of culture has been saved not by great emperors or sophisticated inventions, but by a feline who, in the silence of the night, simply did its duty: guarding knowledge, one paw at a time.