Climate goals depend on China

The world cannot meet its goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100 unless China, the largest polluter, plays a more active and constructive role.

In a nutshell

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- For China, energy security and the economy trump climate protection

- Beijing politicizes energy as its coal-import ban with Australia shows

- One bright spot is China’s record production of renewable energy

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

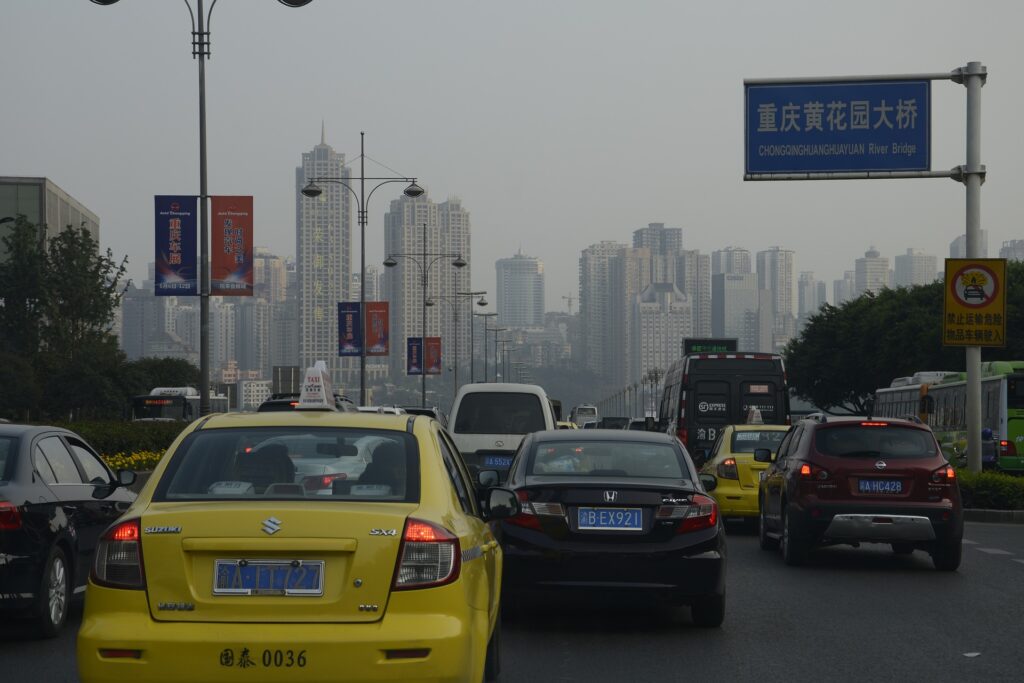

China’s 1.4 billion people account for 19 percent of the world’s population, 22 percent of the global gross domestic product (GDP) and 26 percent of the planet’s energy consumption. In the energy sphere alone, Beijing is the world’s biggest polluter and largest investor in cleaner energy.

China consumes more than half of the world’s coal supply and imports more oil and – since 2022 – liquified natural gas (LNG) than any other nation. At the same time, China sets the pace in solar and wind renewables, is a driver of hydrogen projects and has the world’s largest electric vehicle (EV) and battery market.

Yet Chinese carbon emissions rose to more than 30 percent of the global total during the Covid-19 pandemic before falling slightly to 28 percent in 2022. That translates into 14 gigatons (Gt), more than the combined total of all 38 nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

China seeks decarbonization only by 2060

In September 2020, President Xi Jinping announced that China would commit to full decarbonization and carbon neutrality only by 2060. He reaffirmed the goal at the Glasgow summit in 2021 to reduce national emissions starting in 2030. Until then, China’s emissions can continue to increase annually. For the first time, however, Beijing now wants to reduce its coal consumption and emissions starting in 2025. China also seeks to increase the share of “clean” energy sources (those, according to Chinese interpretation, also include nuclear energy and hydropower) from 15.9 percent in 2020 to 25 percent of primary energy consumption by 2030.

The sheer scale of China’s energy consumption shows that the nation will decide whether the planet meets its goal of holding global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Climate change and consequences

Burning coal and adding renewables like never before

China burns more than 4 billion tons of coal annually, accounting for 58 percent of global demand in 2022. As a result of China’s energy crisis since 2021 and rising LNG and coal prices, China’s coal, oil and gas production soared in 2022. It increased its coal production by 9 percent, to 4.5 billion tons in 2022. Gas production rose 6.4 percent to 218 billion cubic meters (bcm), while crude oil production grew above 200 million tons for the first time since 2015.

Although permitting should not be equated with construction, the 106 gigawatts (GW) of new coal power projects approved in 2022 are astounding. The trend continues in 2023. At least 20.5 GW of new coal-firing power plants were approved in the first quarter. China’s coal generation capacity could reach 270 GW by 2025, more than the coal generation capacity in the United States.

These developments are alarming for global emission reduction efforts, despite China’s addition of a record 125 GW in solar and wind capacity last year. Data since 2021 shows that climate and environmental targets have again taken a back seat to energy security and economic competitiveness.

High demand for natural gas and LNG

Natural gas accounts for only 8 percent of China’s primary energy mix, compared to 23 percent globally. Chinese gas consumption is expected to peak in 2035. Domestic oil and gas production expansion enjoys high priority for curbing imports, which stand at 40 percent of natural gas consumption.

China’s total gas consumption could increase from 320 bcm in 2020 to 340-360 bcm and production is expected to soar to 430 bcm in 2025. Domestic natural gas production rose by 9.8 percent to 189 bcm in 2020, with an expected rise to 220-250 bcm in 2025. Yet China will still need to import an estimated 180-210 bcm of pipeline gas and LNG annually.

In 2025, China might import 38 bcm via the Russian Power of Siberia 1 pipeline and 60 bcm from Central Asia and another 10 bcm from Myanmar via pipelines. Russian gas accounted for just 6 percent of the total gas imports in 2021, though the share increased last year because of the war in Ukraine.

But talks with Moscow for constructing the Power of Siberia 2 (PS-2) gas pipeline, adding an annual capacity of at least 38 bcm (and feeding it with gas from the Yamal peninsula, previously supplied for the now-closed Nord Steam gas pipelines), highlights the increasing power imbalance in favor of Beijing. Russia has lost its most important and profitable European gas market because it invaded Ukraine, and any new pipeline to Asia will take between five to 10 years to complete. Meanwhile, China seeks to double its annual gas imports from Turkmenistan up to 65 bcm. China’s rising needs will result in an LNG import demand of around 80-110 bcm in 2025, which will be fulfilled via 24 LNG import terminals with a current capacity of 136 bcm per year.

Can electric vehicles deliver a just energy transition?

China’s influence on the LNG market

China is the biggest wild card in worldwide LNG demand development, with demand high enough to influence market price. While German and other European gas companies only want to sign new LNG contracts for up to 10 years due to the uncertainties in European Union gas demand by 2030, China has been willing to sign new long-term contracts up to 30 years with Qatar. If Beijing’s demand grows further, the EU may face supply problems as soon as next winter. The International Energy Agency expects China to absorb 80 percent of the additional 23 bcm in LNG supply available this year.

Renewables and future electricity demand

Electricity currently represents around 24 percent of China’s final energy consumption and has been forecasted to almost double, up to 46 percent, in 2050. Rapid urbanization is a major driver. Today, nearly two-thirds of China’s population lives in cities. Over the last two years, China experienced severe power shortages in several regions due to strong demand, unprecedented droughts and bad energy management. In addition, the politically motivated ban on cleaner coal imports from Australia in 2020 triggered local power blackouts. It forced China to increase its domestic production of dirtier and lower-quality coal. (Australia ran afoul of Beijing for, among other things, calling for an international investigation into the origins of Covid-19.)

Betting big on solar and nuclear energy

By 2021, China’s solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity was 306 GW and its wind 328 GW. China also dominates worldwide solar PV production. By 2050, renewable installations are expected to expand further, with solar PV alone up to 1.8 terrawatt-hours (TWh) by 2030 and 5 TWh by 2050.

Also, China plans an expansion of nuclear energy capacities from 50 to 70 GW by 2025, necessitating the construction of about 20 new reactors. The country aims to become the world’s largest nuclear energy operator and is also financing the construction of new nuclear reactors worldwide. Its planned nuclear energy generation of 660TWh in 2050 will be bigger than North America’s capacity. China is building nuclear power plants at much lower costs than its OECD competitors.

Hydrogen (scientifically known as H2 and the element considered a promising energy storage solution) is also expected to play an important role in China’s energy system. By 2030, Beijing targets hydrogen to reach 5 percent and, by 2050, 10 percent of final energy consumption. By 2035, the target is a comprehensive hydrogen energy industry formation.

At the same time, Beijing also embraces a large-scale Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) adoption after 2030. It will need to ramp up its CCUS capacity by more than 400 times up to 1.3 gigatons per year of CO2 by 2060.

Improving energy intensity and energy conservation alone will not be sufficient for a clean energy transition. A significant problem is posed by the fast-growing digital infrastructure, which will more than double by 2030. Energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions will rise along with it, jeopardizing the goal of CO2 neutrality by 2060. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies mainly locate their power-demanding computer mining operations in China, contributing to increases in emissions. The electricity demand could quadruple by 2035.

Another driver of the country’s demand is electromobility. In 2021, some 3.2 electric vehicles (EVs) had been sold in China – 50 percent of the world’s total. It produced 44 percent of the world’s EVs in 2021.

Scenarios

Climate protection as a guiding force

The Made in China 2025 strategy promotes innovation in core sectors such as industry electrification, processing technology and green power. Energy efficiency and low-carbon technologies (such as heat pumps) are also highlighted. Moreover, digitalization for reducing energy intensity in transportation, manufacturing and buildings will play a prominent role also far beyond 2025.

Beijing should be more interested in climate protection since global warming could bring devastating economic consequences for China. With the rise in sea level, the southern coastal provinces of Guangzhou, Dongguan and Shanghai are at risk. Other regions struggle with water scarcity that limits shale oil and gas production and may curb hydropower electricity generation, 16 percent of China’s power mix in 2021.

The clean energy competition is heating up as the U.S. rolls out its Inflation Reduction Act and the EU its Fit for 55 policies under the European Green Deal. However, digitalization technologies open vast opportunities for China, a manufacturing powerhouse. They give rise to new industries such as EVs, batteries or heat pumps and build demand for rare earths and other critical raw materials – another area of China’s strength. Consequently, China’s market share of EVs in Europe is expected to grow rapidly at the expense of its German and other European competitors.

Energy security and economic interests dominate

China’s energy policy has always prioritized the security of supply combined with extensive self-sufficiency and autarky to free itself from import dependencies.

Beijing’s future climate policy will depend on Western geopolitical concessions. That could result in an appeasement policy of the West on the Taiwan question or Beijing’s illegal claims in the South China Sea.

The conflict with Australia has highlighted that Beijing’s interests trump any climate policies. Previously, Australia was the second-most important coal supplier to China after Indonesia, as Australian coal is of higher quality with lower CO2 emissions than China’s. Nonetheless, Beijing was willing to punish Australia with an export ban on coal and other goods and import dirtier coal from South Africa, Indonesia and Russia.

China is far ahead of its competitors’ access to critical raw materials and refinement capacities. It might increasingly benefit from its strategically prudent long-term investments, forcing the West to adopt protectionist policies to reduce its raw material, technology and market dependencies on China.

Author: Dr. Frank Umbach professor, researcher, consultant, European government advisor and prolific author, with expertise in energy security and cybersecurity

Source: