Easter between spirituality and popular customs

The Christian celebration that embraces the mystery of salvation and renews humanity’s hope

The Christian holiday of Easter has origins dating back more than 2,000 years, but some of the symbols of modern traditions derive from ancient pagan beliefs.

Easter is the most important religious holiday for Christians, as it celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ, a fundamental and central event in the Christian faith. Although every Christian denomination celebrates the resurrection, the ways in which it is celebrated can vary.

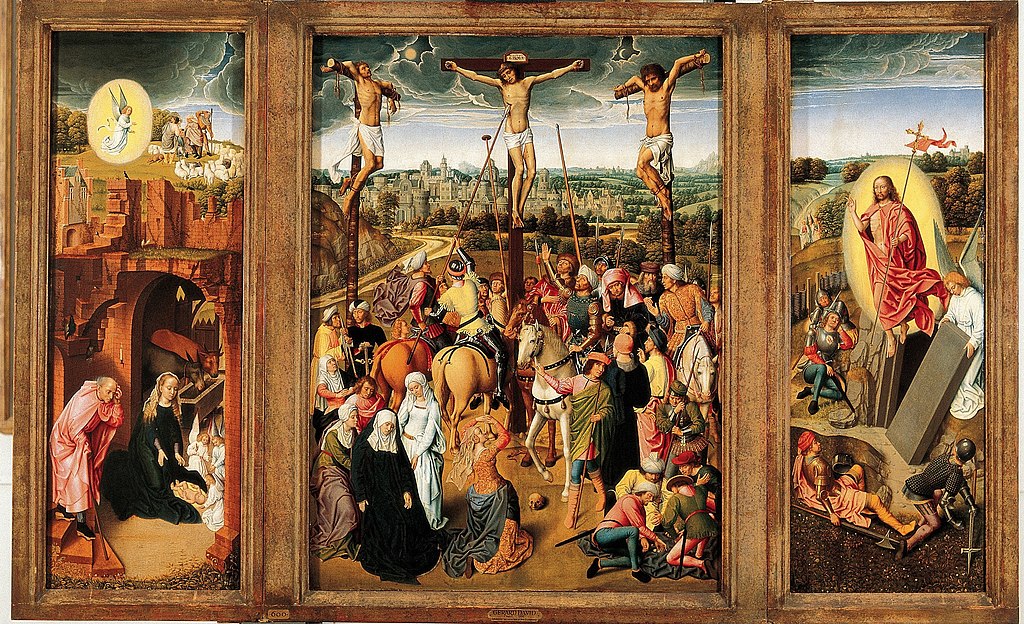

Also known as ‘Resurrection Sunday’, Easter is the main solemnity of Christianity. It commemorates the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, which occurred – according to the Gospels – on the third day after his crucifixion on Mount Calvary, around 30 AD. This event is at the heart of the Christian faith.

Easter marks the culmination of the Passion of Christ, which is preceded by forty days of Lent, a period of prayer, penance and fasting. The week leading up to Easter is known as Holy Week, during which crucial liturgical moments such as Maundy Thursday (commemorating the Last Supper and the washing of the feet) and Good Friday (commemorating the crucifixion and death of Jesus) are celebrated. The Easter cycle continues for fifty days, until Pentecost, which symbolises the outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

A movable feast with deep theological significance

The date of Easter changes every year: it falls on the Sunday following the first full moon of spring, as established by the Council of Nicaea in 325. This is based on a lunisolar calendar, similar to the Jewish calendar, and is also the basis for other liturgical feasts such as Lent and Pentecost.

From a theological perspective, Easter is the heart of the Christian mystery: Christ’s death and resurrection are not just a historical event, but represent the ultimate victory over sin and death, with the promise of new life for humanity. Jesus is the ‘Passover Lamb’, who sacrifices himself for the salvation of mankind, fulfilling the prophecies of the Old Testament. This passage is clearly emphasised by St Paul in his First Letter to the Corinthians:

‘‘Christ died for our sins, was buried and rose again on the third day, according to the Scriptures.’.

Jewish roots and new Christian interpretation

The Christian Passover was born in continuity with the Jewish Passover (Pesach), but differs profoundly from it in meaning: while Jews commemorate the liberation from slavery in Egypt, Christians celebrate the liberation from sin through the cross and resurrection of Jesus. Early Christians reinterpreted the feast in a messianic key, seeing in Jesus the fulfilment of prophecies and the beginning of a ‘new creation’.

The Gospels’ account

The Christian Easter Resurrection is the central event in the narrative of the Gospels and the other New Testament texts: on the third day after his death on the cross, Jesus rises, leaving the tomb empty and initially appearing to some of the disciples, and then showing himself also to the apostles and other disciples.

All the evangelists recount the episode of the empty tomb:

- Matthew, 28:1: ‘When the Sabbath was past, at dawn on the first day of the week, Mary of Magdalene and the other Mary went to visit the tomb.’

- Mark, 16:1: ‘When the Sabbath was past, Mary of Magdalene, Mary of James, and Salome bought aromatic oils to go and embalm Jesus.’

- Luke, 24:10: ‘They were Mary of Maagdala, Joanna, and Mary of James. The others who were together also told the apostles.’

- John 20:1: ‘On the day after the Sabbath, Mary of Magdalene went to the tomb early in the morning, when it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been turned over from the tomb.’

Easter in the Catholic rite

Easter is preceded by a period of spiritual preparation, Lent, which lasts about forty days and begins with Ash Wednesday (except in the Ambrosian rite). This period is dedicated to abstinence, fasting and reflection.

The week before Easter is called Holy Week. It begins with Palm Sunday, which celebrates Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem. On this occasion, palm or olive branches are distributed to the faithful.

The Easter Triduum includes the evening of Holy Thursday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday and culminates with the Easter Vigil on the night between Saturday and Sunday.

Maundy Thursday: the Chrism Mass is celebrated, during which the holy oils (chrism, oil of the catechumens, oil of the sick) are consecrated.

Good Friday: the death of Jesus is commemorated. No Mass is celebrated, but Liturgical Action is held in the Passion of the Lord.

Holy Saturday: is an aliturgical day, without Mass, dedicated to silence and prayer.

Easter Vigil: celebrated at night, liturgically belongs to Resurrection Sunday.

Easter in the Orthodox rite

The Orthodox Easter, celebrated according to the Julian calendar, does not always coincide with the Catholic Easter, which in turn follows the Gregorian calendar, although sometimes the two feasts fall on the same day. It is considered the most important feast in the Orthodox tradition and is celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon of the spring equinox. A week earlier, the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem is celebrated.

Holy Week is marked by strict fasting, with abstention from meat, fish, dairy products and even oil, and on some days people fast completely. On Holy Wednesday, liturgical preparation begins with the commemoration of the Passion, and on Thursday, the Last Supper and First Eucharist are commemorated, as well as the homemade preparation of decorated eggs, Paskha and kulich.

Good Friday is entirely dedicated to the liturgy, culminating in the symbolic ‘burial’ of Christ with a shroud displayed in the centre of the church.

On Holy Saturday, as the days in the tomb are commemorated, there is a lively atmosphere with the blessing of food and the preparation of the big meal. At midnight, the Easter Vigil is celebrated with processions, singing, the ringing of bells and the beginning of the liturgy that lasts until dawn.

On Easter Day, after visiting the graves of the dead, families gather for a rich lunch with traditional dishes and the famous ‘battle of the eggs’.

During the next forty days, people greet each other by saying ‘Christ is risen’ and reply ‘Truly he is risen’.

The Orthodox celebrations combine Christian elements and ancient folk beliefs, such as the custom of wearing new clothes at Easter or getting up at dawn to predict the course of summer. Each day of the Easter season has its own symbolic meaning related to work, worship of the dead or forgiveness between people.

Easter in Protestant rites

Protestant churches use the Gregorian calendar and therefore the dates coincide with Catholic Easter.

Easter in Protestant denominations is one of the most important feasts of the liturgical year, celebrated in all its different traditions as the central moment of the Christian faith: the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Despite the absence of a unified liturgy, many Protestant churches, such as Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican and Evangelical, share a strong emphasis on the preaching of the Word and the spiritual meaning of Easter, rather than on rituals.

Holy Week is experienced with particular intensity especially in Lutheran and Anglican churches, where celebrations such as Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and the Easter Vigil are maintained, while in other evangelical communities the focus is on Resurrection Sunday with festive worship, songs, prayers and dedicated Bible readings.

Lent is not compulsorily observed, but some groups choose to practice fasting or moments of personal spiritual reflection.

In many Protestant churches, Easter is also an occasion for baptisms and welcoming new members, symbolising new life in Christ.

Easter traditions

The most popular symbols of Easter are eggs (today mainly chocolate eggs) and rabbits. The tradition of decorating eggs has ancient origins: during Lent, in fact, it was forbidden to eat them, and at Easter one found oneself with a large quantity of eggs that could no longer be eaten. To preserve them, they were boiled and then decorated.

The egg is a powerful symbol: life is born from it, representing the resurrection of Christ, who was reborn. The rabbit, on the other hand, is an emblem of spring, rebirth and fertility.

The day after Easter, ‘Angel Monday’, also known as ‘Easter Monday’, commemorates the announcement of the resurrection by the Angel.

Easter traditions vary significantly from country to country, reflecting the different cultures and Christian customs that characterise each nation. Here is an overview of traditions in some European countries:

Germany: In Germany, Easter is celebrated with a strong connection to family traditions and folklore. The week before Easter is called ‘Holy Week’, and Good Friday is a day of reflection and silence. One of the most famous customs is the ‘Osterbaum’ (Easter tree), where people hang coloured eggs, flowers and other decorations. In the kitchen, traditional dishes such as ‘Lammbraten’ (roast lamb) and ‘Osterbrot’ (sweet Easter bread) are prepared. Children have fun with egg hunts, a tradition that has also spread to other countries.

Italy: In Italy, Easter is a celebration that combines religion and gastronomy. The most famous symbol is the ‘Colomba di Pasqua’, a traditional cake representing peace. Each region has its own typical dishes, such as roast lamb and the Neapolitan ‘pastiera’. In some cities, such as Florence, the ‘Scoppio del Carro’ is celebrated, an event involving the explosion of fireworks to wish a good harvest. On Palm Sunday, the faithful participate in the blessing of olive branches.

France: In France, Easter is followed by numerous local traditions. Church bells stop ringing from Palm Sunday until Easter, symbolising mourning for the death of Jesus, and then ring again with great joy during the Easter Vigil. A popular tradition is the ‘Chasse aux Œufs’ (egg hunt), which takes place in public gardens and parks. In some regions, such as Provence, typical sweets such as ‘gâteau de Pâques’ (Easter cake) are prepared.

Norway: In Norway, Easter is experienced as a holiday of family relaxation. One curious tradition is “påskekrim” (Easter mystery), which involves reading mystery books or watching mystery movies during the Easter season. Easter cuisine includes dishes such as “lammegryte” (lamb stew) and “påskekake” (Easter cake). In addition, many Norwegians take advantage of Easter to go hiking in the snow or spend time in mountain cabins.

Spain: In Spain, Easter is one of the most heartfelt holidays, with “Semana Santa” (Holy Week) involving numerous religious processions, especially in Andalusia. “cofradías” (religious brotherhoods) carry sacred statues through the streets, accompanied by liturgical songs and music. In some regions, such as Catalonia, they prepare typical sweets such as “monas de Pascua,” which often contain a hard-boiled egg in the center.

Portugal: In Portugal, Easter is a major religious celebration. “Semana Santa” is celebrated with processions through major cities, such as Braga and Porto. “Sábado de Aleluia” (Easter Saturday) is an event marked by singing and dancing in preparation for the resurrection. In the kitchen, dishes such as “cabrito assado” (roast lamb) and “folar,” Easter sweets with hard-boiled eggs, often exchanged between families, are prepared.

Denmark: In Denmark, Easter is celebrated with large family feasts and the tradition of hiding colored eggs in gardens. In addition, Danes prepare “påskebord,” a buffet full of egg dishes, fish and smoked meats, reflecting the country’s rich culinary tradition.

United Kingdom: In Britain, Easter is also an occasion to enjoy typical sweets such as the “Simnel Cake,” a fruit cake decorated with eleven marzipan balls, symbolizing the twelve apostles (excluding Judas). The tradition of “egg rolling” is particularly popular, especially in Lichfield, where children participate in competitions to see who can roll their eggs the farthest without breaking them.

Ireland: In Ireland, Easter is celebrated with religious celebrations and traditional outdoor picnics. “Easter Monday,” known as “St. George’s Day” in some areas, is a day dedicated to family relaxation, often spent outdoors with activities such as walks in parks.

Switzerland: In Switzerland, colored eggs take center stage, and are often exchanged among family and friends. Church bells remain silent from Maundy Thursday to Holy Saturday, symbolizing mourning, then ring festively on Easter night, celebrating Christ’s resurrection.

Traditions in Orthodox countries

Among the most characteristic customs of Orthodox Easter is the tradition of decorating eggs as real works of art. Each country follows its own customs: in Greece hard-boiled eggs are dyed red, symbolizing the blood of Christ, while in Ukraine they make pysanky, eggs decorated with the batik technique, a refined method that involves the use of wax to create complex and symbolic motifs. In addition to eggs, the Orthodox Easter table is enriched with typical sweets such as paskha, a tvorog (cream cheese) dessert in the shape of a truncated pyramid, and kulich, a fluffy cylindrical cake enriched with raisins, candied fruit and almonds, covered with sweetened icing and often flavored with liqueurs.

In conclusion, Easter is a major holiday for Christians around the world, as it celebrates the central event of faith: the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Its roots go back more than two thousand years, but over time it has acquired cultural and traditional meanings that vary from country to country. Between religious rituals, family traditions and symbols such as eggs and rabbits, Easter continues to be a time of spiritual reflection, renewal and celebration of life, uniting believers and nonbelievers in an atmosphere of hope and community.